Poppies and Yams and Pumas, oh my!

At the Djerassi ranch, I’ve been wearing a lucky flower-printed house-shirt, hand sewn by my mother. It lets me play out my fantasy of living out on a prairie or frontier farm—without any of the grueling physical labor. I get to write and read all day, and go on hikes for the span of five weeks. A luxury, indeed! Previously a cattle ranch, the Djerrassi lands are not currently farmed, but Carl Djerassi made his name as “the father of the birth control pill” by working on the synthetic fabrication of a progestin extracted from a farm product, a root vegetable grown by generations of people, across cultures—the yam.

On the road to the property is a sculpture of a mammoth prairie wagon, stuffed with what looks like massive beefy potatoes. This is Anne Weber & William Wareham’s –To Market, To Market (2000)—an ode to root vegetables and earlier generations of U.S. farmers, immigrants trying their luck in a new land. I cannot help but think of Carl Djerassi, himself an immigrant from Austria, and his own fortuitous relationship to a particular root vegetable. (Fields of estradiol. Cycle regulation. The sexual revolution.)

With such colossal sculptures on the hills overlooking barns and sheds, and more intimate art installations popping up in quiet wooded passes, I find myself in that movie of outsized dreams, The Wizard of Oz, where rural life gets thrown into Technicolor by a tornado, a giant vortex—no less. Here with the fog and the ocean and the hills and the artists, it’s more like “rural life” gets doused in some uncanny magic. Oh, there’s a hand coming out of the ground! No, that's a sculpture. Look, a human finger on the trail! On closer examination: dried animal scat. Maybe from a puma?

Djerassi is a land preserve where pumas, or mountain lions, still slink about mainly at night. I think of the Cowardly Lion in his floppy suit. Not at all slinky. In the postindustrial age, our scarecrows reach for brains— with the increasing biomorphic complexity of pesticides— and bots might search for hearts or at least “likes.” But what does a lion’s courage mean in the face of insidious human encroachments on territory: Domesticate or die!

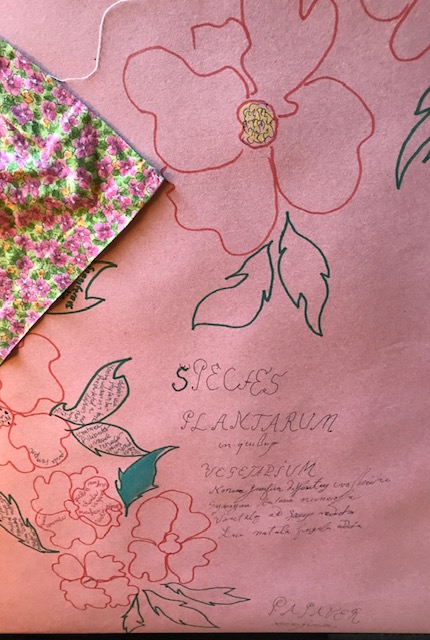

Earlier this year I saw a Louis Vuitton menswear display in London with the theme of the Poppy Field from the Wizard of Oz. Sleek obsidian male mannequins were dressed in black bomber jackets patterned in electric orange poppies, with a narcotized Dorothy nestled within. I loved the look but at the same time that knocked-out Dorothy on men’s loungewear alerted my creep-o-meter. My own lucky prairie shirt is infinitely more shabby, but has a pattern of small pink and magenta flowers. They could as well be poppies. They might be poppies. I look up images of poppies. Yes, they must certainly be poppies! Now if I only had an enamel pin of Dorothy, I’d be in Oz-prairie-chic heaven.

The species of poppy that produces opiates (papaver somniferum) has been cultivated by humans since the Stone Age. It is banned here in the States. The raw materials for medicinal opiates are imported from licensed poppy farms in South and Central Asia, among other places. A sharp claw-like blade is used to incise the seedpod, and a pink milky “latex” is released, then left to dry. The hardened resin is scraped off and further processed. Despite increased international surveillance and pressure, unlicensed farms proliferate in Afghanistan. The production of poppies is banned there too, but the market is too lucrative for farmers—living with constant political and economic instability—to give it up. Root vegetables or rice cultivation simply cannot support their families. It makes sense. Even here in the States with giant mega-industrial farms, the lone family farm operates as a type of frontier—a risky, precarious venture.

So what do I do with poppies? I sit in the grasses (covered in tick repellent) with my poppy field shirt and look for little vortexes. One forms in my hair—a tiny black cyclone—a telescope into another world. Then I start on a poem called “The Oz Machine.”