Leonardo's Strange Angel: Behind the Scenes with Jack Parsons and Frank Malina

A not-so-well-known story of Leonardo's founder, Frank Malina, and "strange angel" Jack Parsons.

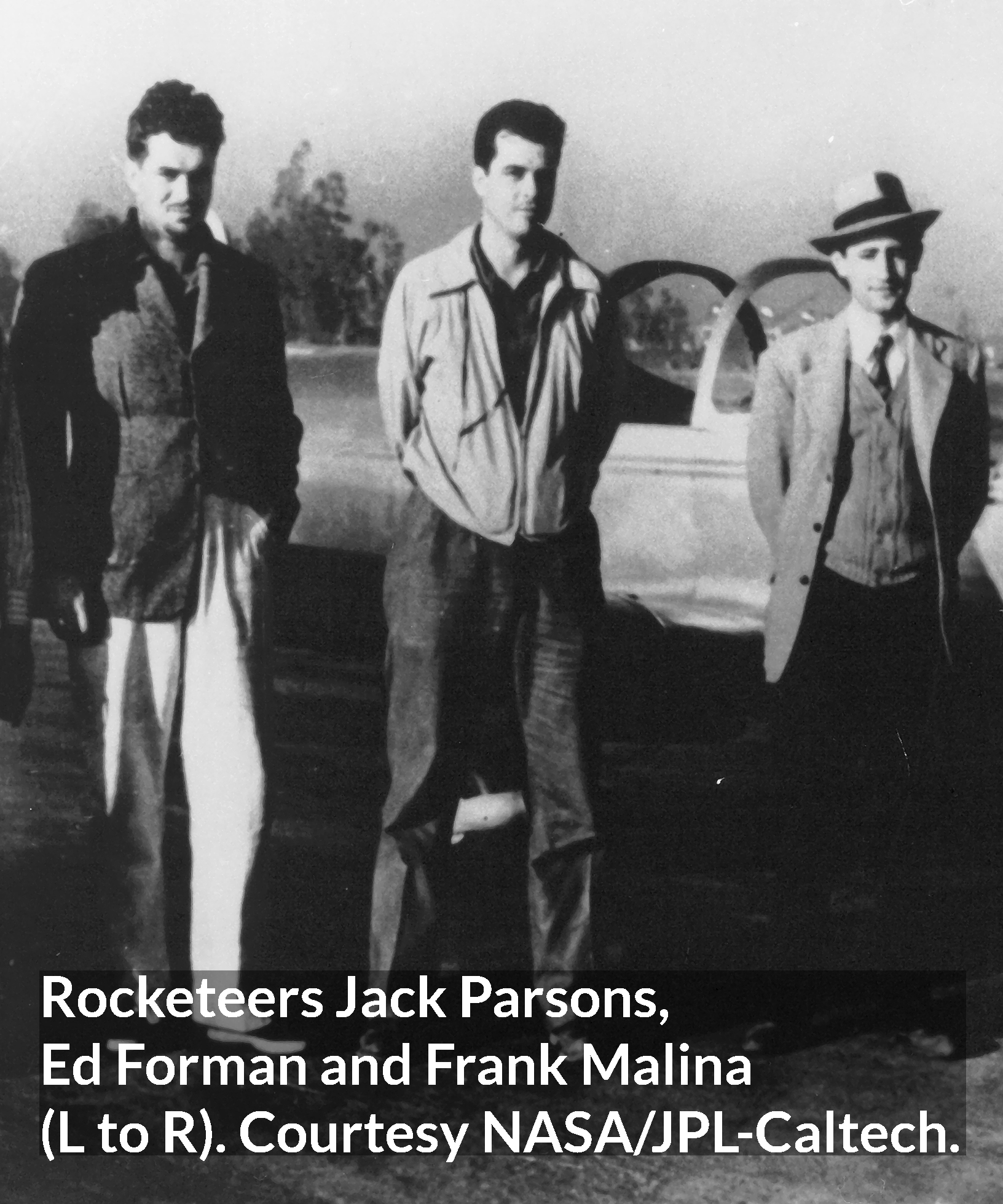

You know you’re desperate when you start writing a screenplay. But that seemed the only option left to Frank Malina and Jack Parsons as they struggled to build their rockets in Pasadena in 1937. Malina, a Caltech aeronautics grad student, was just 25 years old. Parsons, a self-taught chemist, was only 23. They had been brought together two years before by their shared belief that rockets were the only technology that could transport mankind into outer space. In this belief, however, they were quite alone. No university, corporation, scientist, or politician in America thought there was any future in rockets. Most believed that travel off the planet was impossible. There was no money, no facilities, no textbooks to help them. But there was Hollywood.

Seated L to R: Rudolph Schott, Apollo Milton Olin Smith, Frank Malina (white shirt, dark pants,), Ed Forman and Jack Parsons (right foreground). Rocket tests at Arroyo Seco, 15 November 1936. Courtesy NASA.

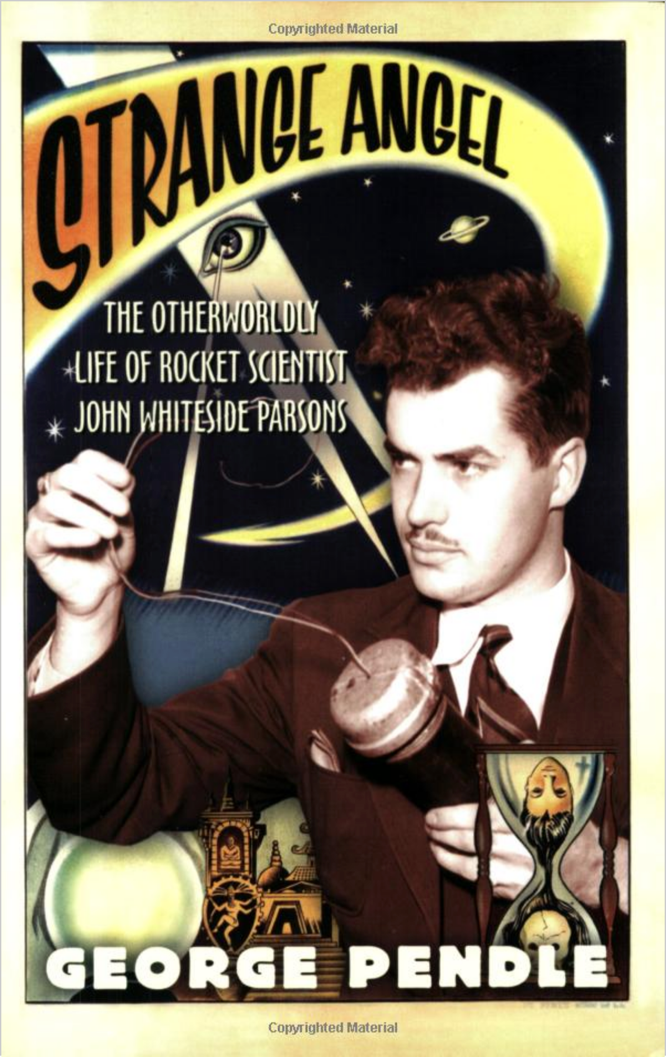

Uncovering the life and work of Jack Parsons for my biography Strange Angel led me down some peculiar routes. Few research projects demand a writer scour the archives of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society, and the Ordo Templi Orientis (an occult group that Parsons headed and that Malina occasionally frequented.) But one of the strangest discoveries was found in the archive of Marjorie Malina, Frank Malina’s wife, in Paris.

Amongst personal correspondence and scientific papers lay a neatly typewritten story, written by Malina and Parsons. It was dated 1937 and scrawled on the front page were the words “MGM Project.” At that time Malina was working as an assistant in the Caltech wind tunnel for pennies an hour, while Parsons had a part-time job at an explosives company. Their pitiful salaries provided all the funding for their rocketry research, and they spent hours scouring scrap yards and rubbish dumps for odds and ends they could use in their experiments. The MGM Project was a Hail Mary attempt to garner movie money to finance their scientific dream.

The story itself is a garish mix of science fiction and social justice, with a dash of occult weirdness thrown in. Laced with the politics of the day, it tells the tale of a bunch of charismatic young men devoted to designing and building rockets. To call it a roman a clef does not quite do it justice, for while it transparently traces the young rocketeers’ scientific struggles and wistful hopes, it also eerily foretells their futures.

Set in “the Institute,” a scientific establishment not unlike Caltech, the story’s hero is Franklin Hamilton, a genius physicist and rocket scientist, whose “black closely cut slightly curly hair” and “good looking, sharply chiseled face” make him a dead ringer for Parsons himself. Thomas Elwood, a union organizer, lover of classical music, and man with a social conscience is the clear doppelganger of Malina. As in real life, the scientists’ greatest problem is a lack of financial backing, and their rocket tests often end in explosions, as did those of Malina and Parsons. But while their real-life work was almost universally ignored, in their fictional world it is being spied upon by powerful, shadowy forces.

Part thriller and part socialist manifesto, the story dashes headlong into espionage, murder, and the intricacies of organized labor. Real life and fictional life diverge when Hamilton and Elwood receive a donation of $100,000 from a wealthy aircraft manufacturer—only to find the manufacturer plans to sell their rocket plans to the Nazis. In the grand denouement the rocket plans are about to leave on a plane for Germany when the scientists knock out the pilot and grab back the blueprints. “Only harm to humanity can at present result from its knowledge,” intones Hamilton gravely. The plans are burned and their rocket prototype is fired into the air to be lost forever.

Parsons and Malina worked on the story every Monday night for at least a year before sending it to MGM. But perhaps unsurprisingly its mix of earnest social realism and hardcore scientific speculation failed to pique the studio’s interest. Nevertheless the story proved to be a strangely prophetic piece of work. In the story Elwood is pilloried for his “un-American beliefs,” as Malina would be later in his life, causing him to leave the United States and relocate to France after the war. Similarly a character in the story with strong occult interests is killed in an explosion, just as Parsons would be in 1952. Perhaps most surprising of all was that the young rocketeers’ story foresaw the Nazis' obsession with rockets, long before the popular press, or indeed the US government, did.

While Hollywood did not come to their financial rescue, Malina and Parsons would eventually receive funding from the US Army, a mixed blessing for the pacifist duo. However with that money they enlarged their experiments and founded the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), what is now the leading center in the world for the robotic exploration of the solar system. While Malina had been dubbed Caltech’s “fantasy expert” in 1937, he was by the end of the war one of the most respected minds on rocketry in the country. Once scornful professors lined up to build rockets with him and Parsons.

Now, on June 14th, the story of Parsons and Malina's early rocket days is finally making it to the screen, in CBS All Access’s new television series “Strange Angel,” based on my book. As with Parsons and Malina's film script, some characters have had their names changed and stories combined (the Malina character is now known as “Richard Onsted”) but Malina and Parsons’s fundamental battle to create a whole new science, in the face of dismissive academics and popular scorn, is to remain the same. Eighty-one years after Malina and Parsons first tried to interest Hollywood in their story, Hollywood is finally getting the message.

George Pendle is the author of Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons published by Mariner Press and being adapted into an original television series by CBS All Access. The series premieres on June 14, 2018. Learn more about George Pendle at www.georgependle.com. Learn more about the early days of Leonardo at www.leonardo.info/history.

Buy Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons at Amazon.com.