Meaning without Borders: likn and Distributed Knowledge

by Ben Syverson (artist, writer, programmer), 1317 W. Erie Street, Chicago, IL 60622, U.S.A. E-mail: ben@bensyverson.com.

ABSTRACT: This paper serves as a narrative companion to likn, an artware application about the nature of knowledge, ideas and language. According to the advocates and engineers of the "knowledge representation" project known as the Semantic Web, electronic ontologies are "a rationalization of actual data-sharing practice"; but where do artists and intellectuals fit into this data-oriented model of discourse? likn critiques the Semantic Web from a postmodern perspective. This account describes how postmodern theory was scrutinized, interpreted and ultimately expressed as "features" in likn.

_____________________________

criticalartware is a collaborative art project that emerged in 2002 as a means to connect certain threads of discussion surrounding 1960s and 1970s video art to present-day new-media practice. The interconnections were evident and exciting to us, but we faced a problem in getting our ideas onto the Web: None of the readily deployable web models seemed satisfying in light of the theories we were drawing upon. Indeed, if we examine the state, even today, of "information architecture" (a regrettable analogy) we might find, with a little imagination, an architecture at the peak of high modernism; a World Wide Web overstuffed with the Miesian rectangularity of hierarchies and keywords. We might find whole cities built on MySQL and PHP---the Cor-ten steel that encourages form to follow function. Looking up at the Sears Tower of Google, amidst an impressive yet naggingly oppressive cityscape, we might scratch our heads and wonder: How in the world has this field managed to avoid postmodernism entirely?

As soon as criticalartware (then consisting of Jon Cates, Blithe Riley, Christian Ryan, Jon Satrom and myself) had formed, we wanted to interview a variety of people, both "mainstream" and "marginalized," and make the interviews available on-line and at public screenings. Because our aim was, and is, to foster critical discussion, it seemed obvious that we needed some discussion platform on the web site. Technologically, this would have been no problem; there were hundreds of available "message board" and "comment" systems. The sticking point came when we realized that in order to begin a discussion about one of the interviews, one of us would first have to put the text into a new message or page, thereby making it the "root" of that discussion; all replies would cascade hierarchically from that privileged, somehow "important" interview. We could foresee what Derrida might have called a "violent hierarchy," in which the subordinated discussion might take on an oppositional relationship to the privileged, "central" site content---a dissociation between theory and implementation too large to accept.

This dissatisfaction reinvigorated my long-dormant interest in an alternative hypertextual environment---"alternative," because I felt hypertext could do more than electrify footnotes. Over time, I would come to see the very term "hypertext" as somewhat redundant; the simple act of interpreting a text is a suggestive process whereby words spontaneously spring connections to multiple "meanings" or associations. All text is necessarily "hyperlinked" by the reader on every reading. In that sense, "hypertext," which positions itself as somehow better than normal text (hyper meaning "beyond"), is misleading, because rather than being more associative and connective than "normal" text, it actually narrows the field of association by cementing certain "chosen" connections. By reifying these curated associations, hypertext heavily colors the interpretive process of reading a text. Another way to put it is that a hypertext will always be more prescriptive and rhetorically charged than the equivalent text stripped of links. It follows that, like any form of rhetoric, the emphasis of the link is equally at home in the service of creative humor, pointed critique or violent control. Any alternative system I built would have to draw attention to this fact.

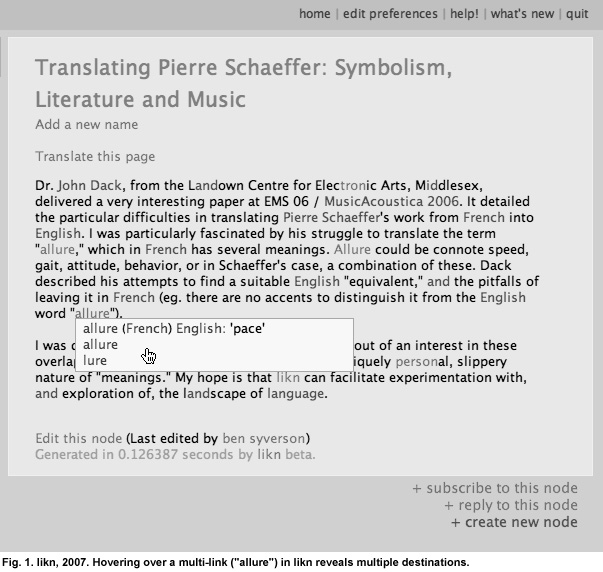

During a particularly stimulating discussion, criticalartware drew up a "wish list" of features for a tailor-made web application. In 2003, I began implementing our ideas in earnest, with an eye toward creating a discussion platform that would itself have something to say. Our initial goals were simple: a generally heterarchical structure, effortless and promiscuous (I simply use easy to connote both) linking to facilitate navigation and intertextual exploration and an open-ended encouragement of unconventional navigational metaphors. I took our interest in easy linking as an excuse to experiment with an idea I had as a boy while developing HyperCard stacks: Given a set of named resources, why not automatically and continually create links to those resources where their names appear in text? With an interesting set of named resources in tow, one could view any electronic text, be it real-time news or an ancient tome, through an ever-changing veil of automatic, in-context links. In other words, if one had a resource (I will call it a "node") named "art," then in any text one viewed, the word "art" would become a link to that node. This almost immediately suggested the need for community editing functionality, so that a term could not become monopolized by a single author. As I began to implement auto-linking, I encountered an interesting problem. Given the nodes "modern art," "modern," and "art," what do I link to when I come across "modern art"? Do I link only to the "modern art" node or to "modern" and "art?" The solution was to implement multiple-destination links. A visual implementation can be seen in Fig. 1. I am also interested in exploring audio cues for the visually impaired.

The Semantic Web

I called the resulting artware liken, a name designed to evoke the layering and hybridity of lichen as well as the associative nature of the software. It served criticalartware well, but at the end of 2004, liken was taken off of the Web and work began on its replacement, likn. The biggest addition we wanted to make was deceptively simple: We wanted a way to add and utilize more "metadata," that is, information about information (for example, "Date posted"). This innocuous-seeming task would necessitate a journey from likn’s origins in deconstructionism to high modernism through structuralism and then post-structuralism, looping back into deconstructionism and postmodernism and, most recently, encountering an intertwined amalgam of postcolonialism, ecology, Buddhist philosophy and "post-Theory." In liken, we had a basic "tag" or "keyword" system, but I was always uneasy about it. Keywords are maddeningly ambiguous (Python: programming language or animal?) and laborious to apply. As a result, I began to look at more sophisticated metadata approaches and wound up diving into the texts of the Semantic Web. With markup languages like Resource Description Framework (RDF), RDF Schema and Web Ontology Language (OWL), it would be possible to set up a situation where one could simply state that a photo was taken on Michigan Avenue, and other facts (such as that the photo was taken in Illinois) could be inferred (deducted via the transitive property and other pre-coded relationships in an OWL "ontology") from that statement. That sounded interesting to me, so I decided to investigate.

In broad strokes, the goal of the Semantic Web project is to map human "knowledge" and "logic" onto formats that can be interpreted (and sometimes [1] evaluated) electronically [2]. This is achieved through the use of "ontologies." The reference to the philosophical concept of ontology is not accidental. Both senses of "ontology" refer to a formal organization of the entities and relationships that make up a reality. In both domains, this prospect understandably raises eyebrows and questions. Traditional ontology is necessarily metaphysical---Heidegger goes so far as to rephrase "ontological" as "onto-theological." Derrida’s "deconstruction" emerged partially as a rejection of these metaphysics; he displaced this ultimate "center" with a celebration of uncertainty and différance [3]. So, we might ask, why "ontology" for the Semantic Web, in this age of what Brian McHale has called "ontological uncertainty"? Defenders will note that there is no central ontology of the Semantic Web, but rather a multiplicity of theoretically local "ontologies." However, the Victorian preoccupations with classification, naming and categorization are impossible to overlook.

In "Semantic Web Revisited," Nigel Shadbolt, Wendy Hall and Tim Berners-Lee restate their case for the Semantic Web. They defend ontologies from critics who see them as too stratifying:

Ontologies are a rationalization of actual data-sharing practice. We can and do interact, and we do it without achieving or attempting to achieve global consistency and coverage. Ontologies are a means to make an explicit commitment to shared meaning among an interested community [4].

This pragmatic appeal seems essentially to say, "Look, we communicate every day, so don’t sweat the différance." It also happens to touch upon every major complaint I have with the Semantic Web and is the perfect background against which to reiterate some of the statements I make in likn.

To begin with, the phrase "data-sharing practice" is an amusingly retrograde way to describe discourse in any field. It has already been demonstrated in the language of philosophy, science and literature that meaning (here imprudently reduced to "data") is not transparently channeled from "writer" to "reader" through language. For the philosophical argument, look to Derrida’s "Structure, Sign and Play" [5]. For the scientific perspective, one can look at more recent work in cognitive science. For example, in Mappings in Thought and Language, the cognitive linguist Gilles Fauconnier sums it up nicely:

- "Language serves to prompt the cognitive constructions by means of very partial, but contextually very efficient, clues and cues. Our subjective impression, as we speak and listen, is that when language occurs, meaning directly ensues, and therefore that meaning is straightforwardly contained in language. This fiction is harmless in many activities of everyday life---buying groceries or going fishing---but may well be quite pernicious in others---trials, politics, and deeper social and human relationships." [6]

It is impressive that even in the sciences, the political implications of an anemic view of language are apparent. Meanwhile, postcolonial theory has permanently complicated the idea of "meaning" in the literary world by drawing attention to the collaborative meaning-making dialog that readers and writers participate in and the implications of where and when those readers and writers are situated. While the Semantic Web project wants to break our "data-sharing practice" into machine-readable chunks, writers like M.A. Syverson [7] are fighting against the assumption "that we can understand composing atomistically, as distinct entities (texts, individual writers, genres, strategies, tasks, decisions, problems, and ‘processes’), rather than as an ecological system with a high degree of integration among its components" [8].

If we can get past the basic "data transfer" model (I cannot), we encounter a stated desire to "rationalize" discourse through the "explicit commitment to shared meaning." In practice, this means that certain terms or concepts are explicitly defined, and users of a Semantic Web ontology must agree on their specific meanings and schematization. It is interesting to note that, on a technical level, OWL (the Semantic Web XML format for describing ontologies) does not support lies, sarcasm, half-truths, disputed "facts," or, most incredibly, even the capability to say who made a statement or when [9]. Unless one builds some proprietary logic, all assertions on the Semantic Web are equal---which ostensibly renders them objective and absolute truths. The community realizes how grave this situation is, and some are quixotically working on a Trust (Faith) "layer" to ride atop the Semantic Web "layer cake." It is telling that the more we try to "rationalize" a discourse, the more Faith is required.

If one disagrees with an ontology, one is free to branch off with one's own. After all, no one is "attempting to achieve global consistency"; ontologies are intended to be provisional and local. However, as Shadbolt et al. also mention, "the Semantic Web we aspire to makes substantial reuse of existing ontologies and data" [10], so keep in mind that while ontologies should be provisional and local, they should also be stable and global. Reuse is specifically encouraged because ontologies are currently very technically difficult (and thus expensive) to build, and the dream of the Semantic Web relies on wide agreement to facilitate interchange and interaction. There is an itchy tension here between local definitions on the one hand and a need for consensus and globally shared meaning on the other. In order to achieve consensus, "ontologies are defined through a careful, explicit process that attempts to remove ambiguity" [11]. Thus, despite an insistence that OWL ontologies are local and decentralized, they apparently rely on a consensual, systematic cleansing of ambiguity and dissent. As Lyotard would say, "When the institution of knowledge functions in this manner, it is acting like an ordinary power center whose behavior is governed by a principle of homeostasis. Such behavior is terrorist" [12].

A Way Forward

I began to wonder if my quest to add metadata to likn was completely hopeless. Was it impossible to move toward a more connective discursive environment without imposing some untenable power structure? Once again, I turned to Lyotard, and once again, he had some specific feature requests for likn:

- "A recognition of the heteromorphous nature of language games is a first step in that direction. This obviously implies a renunciation of terror, which assumes that they are isomorphic and tries to make them so. The second step is the principle that any consensus on the rules defining a game and the "moves" playable within it must be local, in other words, agreed on by its present players and subject to eventual cancellation." [13]

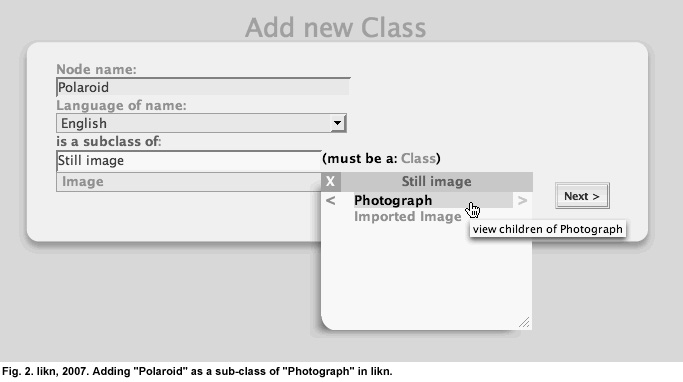

In that case, if OWL ontologies are not local or provisional enough, likn’s ontologies would have to be operational while in a state of flux, allowing people to change the rules of the game as they went along. Semantic connections would have to be easy to create (see Fig. 2), easy to turn off without any vote and easy to restore. They would have to be just as easy as the links. This would help to prevent a marginalizing democracy, but it could easily lead to bickering. I envisioned endless, fruitless infighting over definitions, classifications and categorizations.

The problem thus became how to make likn into an environment that encourages (or even provokes) the sometimes-heated play of questioning, while discouraging what I view as unproductive terminological "border skirmishes" that just bog conversations down. Through working on likn, I have started to view terms as states, in both the physical and political senses. Perhaps I will meet Spivak somewhere in the middle, given that she wanted to "progress slowly into an understanding of ‘culture as translation’" [14]. Like vapor or ice, any given word sense is just a condition of larger continuums or phenomena. The contentious questions are which continuums or phenomena the word sense belongs to and the location of the point of state change. This is where the political sense of "state" becomes useful, as certain "borders" are drawn to keep the meaning of the term in and barbarian senses out. These borders are by definition political, and the struggles to define, defend and challenge them often lead to real blood; Terry Eagleton points out that "fundamentalism is a textual affair" [15]. In recursive fashion, I would note that the term "fundamentalism" itself is charged, as Edward Said mentions:

- "Take as a case in point the emergence of "terrorism" and "fundamentalism" as two key terms of the 1980s. [Both of these] derived entirely from the concerns and intellectual factories in metropolitan centers like Washington and London. . . . These two gigantic reductions mobilized armies as well as dispersed communities." [16]

If words and terms are states with real power, then Said warns us that these states can also be colonized and exploited by imperial concerns. Transnationals create and defend "trademarks," while intellectuals "coin" (attempt to capitalize on) neologisms that are rarely necessary. This terminological market capitalism is nothing new, but it is now hastened by a specific technological metaphor: the "search." The idea is, roughly, that if one wants "information," one must go searching for it [17]. (It is obvious that little thought went into the choice of this metaphor; offline, searching is a laborious enterprise that is frequently frustrating and only sometimes rewarding. Searching is for missing children, rare first editions, a sense of purpose, just the right gift or dropped contact lenses.) Because a "search" is based on the exact characters of the words and terms submitted, what might be relaxed diction takes on a self-conscious gravity. For example, people searching for "sound art" might not be able to find artworks described as "digital sound," and those searching for "digital sound" may be overwhelmed with articles about digital audio recording. Through likn, I wanted to propose that this constant lexical migration and colonization is technologically assisted and is creating false "paradigm shifts" that occlude and obfuscate interesting points of connection in many fields.

While I was thinking about these concerns, I decided to work on a (seemingly) more prosaic technical issue: multiple language support. My idea was to allow people to add multiple names to a node and define the languages of those names---thus there could be a "music" (English) node that also had the names "musique" (French) and "

" (simplified Chinese). Whenever any of those words appeared, they would link to the same node. Of course, we cannot force node names to be unique, because homonyms should be permitted to exist in separate nodes (i.e. one would probably want to separate "billiards" and "pond," but allow "pool" as an English name for both of them). Suddenly, I realized that this meant someone would be able to create an entirely separate music node, borrowing some or all of the names from the original music node. She might do this to offer a different sense of the word "music," a competing definition, or different semantic connections. Perhaps the creators of the first node are not willing, for whatever reason, to accept the assertion "music is a subclass of art." Because both music nodes will automatically show up as destinations for in-context multi-links, there is no need for a power struggle and no need to branch off and maintain two separate ontologies. Instead of "[attempting] to remove ambiguity," which can never succeed, likn specifically invites it as the creative milieu of all intellectual discussion.

" (simplified Chinese). Whenever any of those words appeared, they would link to the same node. Of course, we cannot force node names to be unique, because homonyms should be permitted to exist in separate nodes (i.e. one would probably want to separate "billiards" and "pond," but allow "pool" as an English name for both of them). Suddenly, I realized that this meant someone would be able to create an entirely separate music node, borrowing some or all of the names from the original music node. She might do this to offer a different sense of the word "music," a competing definition, or different semantic connections. Perhaps the creators of the first node are not willing, for whatever reason, to accept the assertion "music is a subclass of art." Because both music nodes will automatically show up as destinations for in-context multi-links, there is no need for a power struggle and no need to branch off and maintain two separate ontologies. Instead of "[attempting] to remove ambiguity," which can never succeed, likn specifically invites it as the creative milieu of all intellectual discussion.This naming multiplicity not only addresses the "border control" problematics but also encourages the modeling and play of analogical associations. How might a community respond when someone adds "cybernetics" as another name for a "new media art" node? These associations can suggest unexpected continuums and connective threads between states ("concepts") that may turn out to be provocative, insightful or absurdly funny fodder for discussion. Some may object that this obscures the actual information, but likn promotes a certain skepticism toward the popular conception of "information." The word itself has some unsavory connotations; in English, to "inform" means, more or less, to enlighten, betray or influence. With a didactic hierarchy, the whiff of treachery and an implication of Truth all wrapped up in one word, "information" starts to sound pretty unappealing from a postmodern perspective. There are surely other ways of approaching the term; Gregory Bateson offers a famous definition of information as "a difference that makes a difference." In popular usage, however, "information" seems to be established as synonymous with "data" or even "fact." This is, at the very least, a distorting reduction of the complex process of human communication. Artists and intellectuals would be wise to approach the phrase "information technology" as cautiously as they might approach the phrase "global capitalism."

The Present State

The road trip of likn has been long and rocky, as I have attempted to chart a philosophical and theoretical route to a more artistically and intellectually satisfying approach to metadata. Looking again at the Semantic Web conception of ontology, it seems to me that it represents an increasingly common but unrewarding retreat from the play of discourse in postmodernism to a hastily assembled pragmatic foundationalism. This foundationalism recognizes the philosophical and scientific impossibility of foundations, yet throws its arms up and says, "Well, what else can you do?" In their brilliant work The Embodied Mind, Varela, Thompson and Rosch describe the root of the conflict as "Cartesian anxiety": "The anxiety is best put as a dilemma: either we have a fixed and stable foundation for knowledge, a point where knowledge starts, is grounded, and rests, or we cannot escape some sort of darkness, chaos, and confusion" [18].

If we do not recognize this as a false dichotomy, the natural tendency is to turn to some kind of pragmatism, since, as Shadbolt et al. point out, "We can and do interact." This pragmatism very quickly asserts a "provisional," "local" or "practical" foundation. Anything can be built on a foundation that has pretensions of being provisional or commonsensical, because no justification or legitimation is required. Unfortunately, self-justification is a disastrous response to the false dichotomy of absolutism/nihilism. Rorty writes, "The rhetoric we Westerners use in trying to get everybody to be more like us would be improved if we were more frankly ethnocentric, and less professedly universalist" [19]. In 1999, years before the United States radically expanded its frankly ethnocentric mission to "spread freedom and democracy" [20], Spivak accurately predicted that Rorty’s philosophy "can undoubtedly offer an even more convenient excuse for military activity and exploitation than the argument from universalist rationality" [21].

Similarly, the Semantic Web wants to give World Wide Web users foundations on which to "rationalize" their "data-sharing practice," but creative people all over the world are currently debating the value of this prospect. I recently attended the MusicAcoustica 2006 conference (for which this paper was originally written) and was astounded that academics, artists and musicians in the field of electroacoustic music were so actively engaging this exact question. Leigh Landy proposed in his paper that the field should enter into a discussion about the definitions and meanings of their terms. As he notes in his abstract,

1) current terminology usage in the field is at best fluid and at worst in a fairly weak state, especially category and genre terminology; and 2) the field of Electroacoustic Music Studies (EMS), instead of engaging in foundational issues that have yet to be resolved, tends to focus on aspects of investigation at higher levels [22].

This thirst for resolution and categorization often leads people to the Semantic Web. Yet Kenneth Fields, who is leading the effort within this field to build an OWL ontology named Digital Audio Ontology (DAO), raised some of the most pointed questions of the conference:

Though great benefits to the web masses have been predicted by semantic web visionaries, it remains to be seen if an electronic music ontology will in fact have any practical benefits for our professional community. . . . Will formalisation of concepts kill the fun for the majority of academics who fear standardisation and cling to a supposed fecund ambiguity? [23]

In likn, I argue for ambiguity, fluid terminology and "higher-level" investigation, all without sacrificing semantic modeling and connectivity. Any stable "foundation" would be impossible and wholly undesirable.

Well, one might ask, if the Semantic Web is so problematic for academics, who is it for? The Semantic Web openly aims to be a platform for advancing globalization (in the social as well as economic sense) and transnational capitalism. This may be counterintuitive for some who see postmodernism as the language of global capitalism, which would make likn seem allied to some form of "pure capitalism." Adopting this critique of postmodernism, Eagleton writes that "a radical assault on fixed hierarchies of value merged effortlessly with that revolutionary levelling of all values known as the marketplace" [24]. However, a truly unstructured marketplace could only be local. In order to be global, a company needs "an explicit commitment to shared meaning," so that various component parts of the company can be coordinated. It requires some pragmatic absolutism; some "provisional" or "practical" foundations with which to build hierarchies. Look, for example, to the single greatest success story of the Semantic Web: the work being done by the W3C Semantic Web Health Care and Life Sciences (HCLS) group. As they put it (emphasis in original),

HCLS will actively coordinate with groups and consortia within Life Sciences and Health Care areas:

Health Care, Clinical and Life Science Consortia

Research Institutes and Centers

Pharmaceuticals and Biotechnology Companies

IT Solution Vendors

Government Agencies [25]

This exemplar of the Semantic Web must be very impressive to business executives---and, to be fair, perhaps the HCLS will even lead to some life-saving breakthroughs. I am less sure that many academics will be impressed with a system that loudly touts its ability to seamlessly connect governments with "Big Pharma," or lets "IT Solution Vendors" peddle their wares to biotech companies with greater ease. At the very least, it lacks the playful intellectual appeal of the early days of the Web.

It seems to me that postmodernism is a critique---not the language or logic---of this global system that the Semantic Web hopes to support. Even Eagleton must later recognize that the nature of global capitalism is somehow antithetical to postmodernism:

With the launch of a new global narrative of capitalism, along with the so-called war on terror, it may well be that the style of thinking known as postmodernism is now approaching an end. It was, after all, the theory which assured us that grand narratives were a thing of the past [26].

My Lyotardian leanings give me only a skepticism of grand narratives, not some fantasy that they are extinct. Furthermore, the pragmatic foundationalists’ entitled and self-justified response to these grand narratives (in After Theory, Eagleton advances a moral argument founded on a return to "Truth, Virtue and Objectivity," in the words of one chapter title) does not compare favorably to the postmodern reaction, which is to continually raise questions and problematize the simplistic. This sort of questioning was the impetus for likn, and now, after two years of exploration, involving many theories and technologies, I am even more attracted to postmodernism, which seems to offer many fresh and viable avenues to explore.

I am currently running down many of these avenues, as likn only raises questions while impishly deferring conclusive answers. Beyond criticalartware’s installation of likn, I plan to set up likn for several very different on-line communities and I am curious to see what will emerge. How will people take to likn as a research tool? Will it be a fertile medium for discussion? Will likn defuse terminological immigration anxiety, or, in a perverse turn, will it just methodically expose irreconcilable differences between colleagues? One hopes these questions will lead to better ones as more people interact with and within likn installations. As a functional but experimental artware text about knowledge, likn is in the curious position of being able to incorporate responses to itself, so on behalf of criticalartware, I invite you to continue the discussion by joining us at http://likn.criticalartware.net/.

References and Notes

1. Only certain varieties of Semantic Web "ontologies" offer computational guarantees about how long an inference could take to resolve. OWL-Full, the most expressive of the Semantic Web technologies, offers no guarantee; evaluating an expression using OWL-Full could take any length of time.

2. See http://www.w3.org/2001/sw/.

3. Jacques Derrida, "Violence and Metaphysics," in Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1978).

4. Nigel Shadbolt, Wendy Hall and Tim Berners-Lee, "The Semantic Web Revisited," IEEE Intelligent Systems (May--June 2006) pp. 96--101.

5. Jacques Derrida, "Structure, Sign and Play," in Derrida, Writing and Difference [3].

6. Gilles Fauconnier, Mappings in Thought and Language (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997) p. 187.

7. There is a relation; she is my mother.

8. Margaret A. Syverson, The Wealth of Reality: An Ecology of Composition (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois Univ. Press, 1999) p. 44.

9. This is not strictly true: One can, more or less, make the assertion "Brenda says ‘wormholes are dangerous’"---by describing the "inner" statement (wormholes are dangerous) and attaching information (such as the author) to it in RDF/OWL. It is known in Semantic Web jargon as reification. However, in a deliciously ironic turn of events, by "reifying" a statement in RDF, one renders it false. So only the outer statement (Brenda said X) can be taken to be "True." As soon as we start to drill down and analyze a statement, the simplistic view of "Truth" breaks down instantly, and it becomes clear how slippery our words are.

10. Shadbolt et al. [4] p. 100.

11. Shadbolt et al. [4] p. 100.

12. Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1984) p. 63.

13. Lyotard [12] p. 66.

14. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press) p. 404.

15. Terry Eagleton, After Theory (Cambridge, MA: Basic Books, 2003) p. 202.

16. Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage Books) p. 311.

17. In likn, it is possible to subscribe to nodes of interest via RSS. There are several import modules that can convert blog posts (RSS) and listserv messages into likn nodes. These imported nodes are embedded with in-context links just like any other node, and the presence of these links results in an update being added to the RSS feed for the link destinations. Imagine that one is subscribed to "music," and "musique concrète" is defined as a subclass of music. The "music" subscription would be updated when a listserv message came through that mentioned "musique concrète."

18. Francisco J. Varela, Evan T. Thompson and Eleanor Rosch, The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992) p. 140.

19. Quoted in Spivak [14] p. 367.

20. This language is pervasive in the Bush White House, but see, http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2004/06/20040601-2.html for one example.

21. Spivak [14] p. 367.

22. Leigh Landy, "Electroacoustic Music Studies and Accepted Terminology: You Can't Have One Without the Other," MusicAcoustica 2006, Beijing, China, 23--26 October 2006.

23. Kenneth Fields, "Terminology," MusicAcoustica 2006 [22].

24. Eagleton [15] p. 68.

25. http://www.w3.org/2001/sw/hcls/.

26. Eagleton [15] p. 221.

Manuscript received 22 January 2007.

Ben Syverson is a self-employed artist, writer and programmer living in Chicago.

Updated 30 January 2008

Leonardo On-Line © 2008 ISAST

http://leonardo.info

send comments to isast@leonardo.info